|

|

|

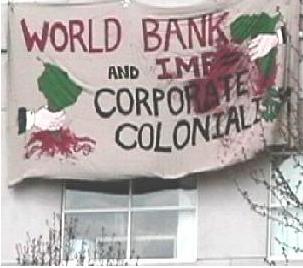

IMF Rescue Cure Worse Than Disease An internal IMF study reveals the price 'rescued' nations pay: dearer essentials, worse poverty and shorter lives. IMF Ecuador Interim Country Assistance Strategy, a sad tale amoung many. Inside the Hilton, Professor Anthony Giddens told an earnest crowd of London School of Economics alumni that 'globalisation is a fact, and it is driven by the communications revolution'. Globalisation, Giddens seems to say, is about giving every villager in the Andes a Nokia internet-enabled mobile phone. What puzzled me is why anyone would protest against this happy future. So I thumbed through my purloined IMF Strategy for Ecuador seeking a chapter on connecting the country's schools to the world wide web. Instead, I found a secret schedule. By 1 November this year, it says, its government is ordered to raise the price of cooking gas by 80 per cent. It must eliminate 26,000 jobs and halve real wages for the remaining workers by 50 per cent in four steps in months specified by the IMF. It must begin to transfer ownership of its biggest water system to foreign operators by July and grant BP's Arco subsidiary the right to build and own an oil pipeline over the Andes. That's for starters. In all, the IMF's 167 loan conditions look less like an assistance plan and more like a blueprint for a financial coup d'etat. The IMF would say it has no choice. Ecuador is broke, thanks to the implosion of its commercial banks. But how did Ecuador, an Opec member with resources to spare, end up in such a pickle? For that, we have to turn back to 1983, when the IMF forced its government to take over the soured private debts owed by Ecuador's elite to foreign banks. For this bail-out of US and local financiers, Ecuador borrowed $1.5 billion. To repay this loan, the IMF dictated price hikes for electricity and other necessities. And when that didn't drain off enough cash, yet another assistance plan required the state to eliminate 120,000 jobs. Furthermore, while trying to meet the mountain of IMF obligations, Ecuador foolishly 'liberalised' its tiny financial market, cutting local banks loose from government controls and letting private debt and interest rates explode. The IMF and the World Bank have lent a sticky helping hand to scores of nations. Take Tanzania. Today, 1.4 million people there are getting ready to die. They are the 8 per cent of the nation's population who have the Aids virus. The financial 'rescuers' found a brilliant neo-liberal solution: require Tanzania to charge for hospital visits, previously free. This cut the number of patients treated in the three big public hospitals in the capital, Dar es Salaam, by 53 per cent. The financial cures must be working. The same bodies told Tanzania to charge school fees. Now the bank expresses surprise that school enrolment is down from 80 per cent to 66 per cent. Altogether the Bank and IMF have 157 other helpful suggestions for Tanzania, and the Tanzanian government secretly agreed last April to adopt them all. It was sign or starve. No developing nation can borrow hard currency without IMF blessing (except China, whose output grows at 5 per cent a year thanks to it studiously following the reverse of IMF policies). The IMF and World Bank have effectively controlled Tanzania's economy since 1985. Admittedly, when they took charge they found a socialist nation mired in poverty, disease and debt. Their experts wasted no time in cutting trade barriers, limiting government subsidies and selling off state industries. This worked wonders. According to bank-watcher Nancy Alexander of the Washington-based Globalisation Challenge Initiative,in just 15 years Tanzania's GDP has dropped from $309 to $210 per capita, the literacy rate is falling and the rate of abject poverty has jumped to 51 per cent of the population. Yet somehow the bank has failed to win over the hearts and minds of Tanzanians to its free-market gameplan. Last June, the bank reported in frustration: 'One legacy of socialism is that most people continue to believe the state has a fundamental role in promoting development and providing social services.' The World Bank and the IMF were born in 1944 with simple, laudable mandates: between them to fund post-war reconstruction and development projects and lend hard currency to nations left skint by temporary balance of payments deficits. But in 1980 they seemed to take on an alien form. In the early Eighties, Third World nations, haemorrhaging after the fivefold increases in oil prices and a similar jump in dollar interest payments, brought their begging bowls to the two bodies. But instead of debt relief, they received structural assistance plans listing an average of 114 'conditionalities' in return for capital. The particulars varied from nation to nation, but in every case, they had to remove trade barriers, sell national assets to foreign investors, slash social spending and make labour 'flexible' (that is, crush unions). What have the IMFers accomplished with their free-market prescriptions? An article by Samuel Brittan in last week's Financial Times declared that the new world capital markets and free trade have 'brought about an unprecedented increase in world living standards'. Brittan cites the huge growth in GDP per capita, life expectancy and literacy in the less developed world from 1950 to 1995. Now hold on a minute. Until 1980, virtually every nation in his survey was either socialist or welfare statist. They were developing on the 'Import Substitution Model', by which locally-owned industry was built through government investment and high tariffs, anathema to the neoliberals. In those dark ages of increasing national government control and ownership (1960-1980), per capita income grew by 73 per cent in Latin America and by 34 per cent in Africa. By comparison, since 1980, Latin American growth has come to a virtual halt, growing by less than 6 per cent over 20 years - and African incomes have declined by 23 per cent. Now let's count the corpses. From 1950 to 1980, socialist and statist welfare policies added more than a decade of life expectancy to virtually every nation on the planet. From 1980 to today, life under structural assistance has become brutish and shorter. Since 1985, the total number of illiterate people has risen and life expectancy is falling in 15 African nations. Brittan attributes this to 'bad luck, [not] the international economic system'. In the former Soviet states, where IMF and World Bank shock plans hold sway, life expectancy has plunged, adding 1.4 million a year to the death rate in Russia alone. Admittedly, the World Bank and IMF are reforming. The dreaded structural assistance plans have been renamed 'poverty reduction strategies'. Spin, the answer to everything in the global economy. Recently, the IMF admitted that 'in the recent decades, nearly one-fifth of the world population have regressed' - arguably 'one of the greatest economic failures of the twentieth century.' And that, Professor Giddens, is a fact. . . . .nd to poverty. These foot-soldiers are mobilisi |