|

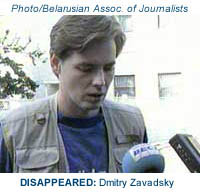

Dangerous News Of the 26 journalists killed for their work in 2000, according to CPJ (Committee to Protect Journalists) research, at least 16 were murdered, most of those in countries where assassins have learned they can kill journalists with impunity. This figure is down from 1999, when CPJ found that 34 journalists were killed for their work, 10 of them in war-torn Sierra Leone. In announcing the organization's annual accounting of journalists who lost their lives because of their work, CPJ executive director Ann Cooper noted that while most of the deaths occurred in countries experiencing war or civil strife, "The majority did not die in crossfire. They were very deliberately targeted for elimination because of their reporting." Others whose deaths were documented by CPJ appear to have been singled out while covering demonstrations, or were caught in military actions or ambushes while on assignment. CPJ researchers apply stringent guidelines and journalistic standards to determine whether journalists were killed on assignment or as a direct result of their professional work. By publicizing and protesting these killings, CPJ works to help change the conditions that foster violence against journalists. The death toll that CPJ compiles each year is one of the most widely cited measures of press freedom in the world. Fewer journalists killed or arrested than in 1999. Nearly three hundred media censored. 26 journalists killed 329 journalists arrested 510 journalists threatened or harassed 295 media censored 77 journalists imprisoned Burma, China, Iran, and Ethiopia are the largest prisons for journalists in the world. In comparison, in 1999, there were : 36 journalists killed 446 journalists arrested 653 journalists threatened or harassed 357 media censored In the year 2000, 26 journalists were killed while practising their profession or for their opinions, 329 were arrested, 510 were attacked or threatened and 295 media were victims of censorship. On 4 January 2001, 77 journalists were in jail (compared to 85 on 1 January 2000) for wanting to freely practise their profession. Close to one third of the world's population is living in countries without any press freedom. Journalists victims of rebel groups or local mafia In 2000, 26 journalists were killed while practising their profession or for expressing their opinions. This figure is lower than that of 1999 (36 journalists killed). 22 of them were murdered because of their work. The four others died in attacks or bomb explosions while they were reporting, without it being clear whether they were direct targets. Eleven journalists were murdered by rebel groups or independence movements in situations of armed conflict against the government. This was notably the case in Sierra Leone, where once again, three journalists were killed by Revolutionary United Front rebels at war against the Freetown government. Similarly, in Sri Lanka two reporters were killed during the year. While their murderers have not been identified, it seems that one of them, Anton Mariyadasan, was killed by the Liberation Tigers of the Tamil Eelam at war against the government. The other journalist, Myilvaganam Nimalrajan, who regularly works for the BBC, was investigating the activities of the Eelam People's Democratic Party, a Tamil movement fighting with government forces against the Tamil Tigers. In Colombia two journalists - Juan Camilo Restrepo, director of the community radio station Galaxia Estereo, and Gustavo Ruiz Cantillo, journalist with Radio Galeó - were murdered by paramilitaries from extreme right-wing groups fighting against communist guerrilla movements. Both journalists had denounced the corruption and violent methods of the paramilitary groups. As the conflict becomes more radical, journalists are increasingly considered to be "military objectives", by both guerrilla movements and groups supported by the army. In Spain, José Luis López de Lacalle, chronicler and member of the regional editorial committee of the daily El Mundo in Basque Country, was assassinated on 7 May 2000. This murder was part of a series of increasingly violent attacks against civil society by the armed independence organisation Euskadi ta Askatusuna (ETA). Media and journalists are regularly threatened or criticised on the "black lists" published by movements close to ETA. Four other journalists, all in Asia, were killed by mafia groups or drug traffickers. In Pakistan, for example, Soofi Muhammad Khan, from the daily Ummat, was shot dead in May 2000 in the south of the country. A few days later police stated that they had arrested the three murderers, in particular Ayyaz Khattak, a notorious drug trafficker. The 38-year-old journalist was investigating the criminal activities of the local mafia implicated in the heroin trade. In many countries impunity remains the rule in cases of murders of journalists. For example, in Burkina Faso those responsible for the murder in December 1998 of journalist Norbert Zongo have still not been punished. When Reporters Sans Frontières planned to visit Ouagadougou on the occasion of the second anniversary of his death, members of the organisation were refused a visa by the Paris embassy. The only satisfying news in this respect comes from Argentina where, three years after the murder of photographer José Luis Cabezas, those responsible have been sentenced to life imprisonment. 77 journalists imprisoned Over half the journalists imprisoned in the world are in only four countries. The largest jails for journalists are Burma (13 journalists in jail), China (12), Iran (9) and Ethiopia (9). In China, 12 journalists were given heavy jail sentences, usually for "counter-revolutionary propaganda" or "subversive activities". Four of them have been detained since the Peking repression in the spring of 1989. Another journalist, Wu Shishen, with the Hong Kong daily Express and the news agency Xinhua, was sentenced in 1992 to life imprisonment. In Iran, two journalists, Hassan Youssefi Echkevari, of the monthly Iran-é-Farda, and Khalil Rostamkhani, of the Daily News, are likely to be sentenced to death. Both are accused of being "mohareb" (fighters against God) for writing or distributing articles which could undermine "national security". In other countries, many journalists were jailed in 2000, often without any explanation. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, 25 journalists were detained at some stage during the year. In most cases they were arrested by one of the nine security services in charge of "national security". Some of them were beaten up, maltreated or even whipped during their detention in one of the numerous jails in Kinshasa or other large towns in the country. In Cuba, where three journalists are still in jail, 22 members of the press were arrested in 2000. They are part of the hundred or so independent journalists considered by the authorities to be "counter-revolutionaries" and who remain a favourite target of repression. Conditions of detention of certain prisoners remain deplorable. In Burma, prison authorities have refused medical care for several journalists. San San Nweh started her seventh year of detention in her ten-square-metre cell in the women's section of Insein jail in Rangoon. She is serving a ten-year sentence for "spreading information harmful to the state". Prison authorities have repeatedly refused her the medical treatment she needs. She is suffering from high blood pressure and a kidney infection. Prisoners in her section are forced to sit cross-legged on the ground with their heads bowed from 6 a.m. every day. Once a day, for 15 minutes, inmates are taken to the "shower" where they are allowed to talk. In Syria, two journalists in prison have similarly been refused medical treatment. Nizar Nayyouf, who worked for the magazines Al-Huriyya and Al-Ma'arifa, has been detained since 1992. He is suffering from serious digestive problems, fractured vertebrae and deteriorating eye-sight, and can no longer walk without crutches. His condition is the result of repeated torture throughout his detention. About twenty media censored every month Close to 300 media were censored or suspended in 2000, primarily in Iran and Turkey. In a single year the Iranian courts, dominated by the conservatives, have closed over 30 reformist publications. On 23 April, they ordered the suspension of nine dailies (including Asr-é-Azadegan and Fath), three weeklies and the fortnightly Iran-é-Farda. In a communiqué published by IRNA, the official news agency, the courts affirmed that closure of these newspapers had been decided to "allay the concerns of the people, the Islamic Republic guide and the clerics". In Turkey the RTÜK, the broadcasting regulatory authority, suspended tens of radio stations and television channels for a total of over 4,200 days. Most of the time these media were accused of "incitement to violence, terror and ethnic discrimination". One Istanbul station, Özgür Radyo, was suspended for two and a half years, mainly for claiming that Rauf Denktash, president of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (recognised only by Turkey) owned "a very substantial amount of real estate in the north of the island" and received money from "gangs involved in prostitution". In Morocco, on 2 December, the minister of culture and communication announced the "definitive banning" of three weeklies, Le Journal, Assahifa and Demain, for "undermining state security". Le Journal and Assahifa published a letter attributed to the former opponent Mohamed Basri, stating that the Moroccan left-wing had been involved in an attempted coup d'état in 1972 against King Hassan II, in which the current prime minister Abderrahmane Youssoufi was directly implicated. Journalists taken hostage During the year several journalists were taken hostage by armed rebel groups. In Colombia, close to 20 journalists were kidnapped by guerrilla movements, usually to protest against their coverage of the war. In the Philippines, between 13 May and 20 September, 25 journalists were held hostage on Jolo Island by the rebel group Abu Sayyaf. Two journalists with the French TV channel France 2 were held for over two months before managing to escape. Another significant release in 2000 was that of Brice Fleutiaux on 12 June. On his arrival in Paris he stated that he had been "detained by different groups" and "had experienced very difficult times but had not been tortured". The French photographer had been detained in Chechnya since October 1999. The Internet under control While the Internet remains a formidable tool for getting round censorship (e.g. the Tunisian newspaper Khalima, published on line after being banned in the country), more and more governments are trying to set up systems to control this means of communication. The elimination of private access providers is one of the methods used. Thus, in Turkmenistan, in May 2000, the telecommunications minister withdrew the licences of all private Internet access providers for alleged "violations of the law". The state can now screen sites and make certain sites inaccessible for Internet users in the country. It also controls all e-mail circulating in the country. In Tunisia, the only two access providers are in the hands of the president's family or close friends. A Chinese court sentenced Qi Yanchen, editor-in-chief of the on-line magazine Consultations, to four years in jail. This is the heaviest sentence passed on a "cyber-dissident". He has been detained since 2 September 1999. Two other Chinese Internet users have been detained without trial. In 2000, the Chinese government promulgated new laws making the dissemination of "subversive" information on the Internet an offence. In Ukraine, the director of an on-line publication has been missing for three months. On 16 September, Géorgiy Gondadze, founder and editor-in-chief of the newspaper http://www.pravda.com.ua - highly critical of the government - disappeared while his wife and two daughters were expecting him at home. The journalist had already been questioned several times by the police in connection with a criminal investigation. Shortly before his disappearance, in a letter to the state prosecutor, he had denounced what he considered to be "premeditated intimidation to scare him or put a stop to his activities". On his site, he published articles denouncing corruption among certain senior officials in Ukraine. A decapitated body found in November 2000 in the Taraschanskyi region near Kiev could be his. The results of the analyses requested have still not been revealed. All indicators (journalists murdered, arrested, attacked and threatened and media censored) are down from 1999. The number of journalists currently in jail is also the lowest in years. The number of countries in which no press freedom exists is steadily decreasing. Yet in about 20 countries in the world the state continues to harass journalists, jailing and torturing them simply because they have written, recorded or spread reports or results of investigations that displease the authorities. The prevailing impunity as regards murders or arrests of journalists remains extremely worrying. Putting a stop to this impunity should be a priority in the next few years.d. .

|